Published

14th August 2023

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly – 14th August 2023

Summer markets

On the face of it, last week contained many of the news headlines that market optimists had been waiting for: rapidly falling US inflation and a cooling jobs market. In the UK, news that four of its major high street lenders were lowering mortgage rates was then followed by confirmation that GDP growth was positive rather than stagnant in the second quarter.

Yet the erratic yo-yo trading pattern of volatile markets over last week would suggest to the outsider that bad news had dominated. So, how are market actors pricing the news flow at the moment, and what, if anything, has changed?

Active investors are a pretty diverse bunch; different people with differing views, approaches, time frames and interests. However, one shared trait appears to be that in aggregate they are quite astute. Active investors are good at taking the available information and judging how and where things are going.

Commentators often talk about what is ‘discounted in the market’ but, oddly enough, it is difficult to know what is factored in until we get the next piece of information. Only then, by looking at the subsequent changes in asset prices, can we tell whether this was really new information or just corroboration of what we knew before.

Indeed, last week was one where we had such an instance. Last Thursday, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics released its consumer price index (CPI) inflation data for July, and it was relatively benign. In particular, the core CPI measure (with food and energy taken out) was +0.16% for the month, and the same as June’s datum. For the two months, annualised core CPI is now running below 2%, at +1.92%.

When the June data was released last month, it defied economist predictions (the average expectation was

+0.3%) and the bond and equity markets reacted as one might expect. In the following 36 hours the 10year yield went from 3.95% to 3.75%, and the S&P500 rose 3% over 48 hours. The market narrative was that this would enable the US Federal Reserve (Fed) to keep interest rates on hold for the near future, with the prospect that they could start cutting next year.

The July data again surprised (economists were expecting +0.22%) and commentators repeated the June narrative: the Fed will be able to stop raising rates and then begin cutting next year. The bond market had seen a dip in yields as the data was about to be released but, immediately after, yields rose. The 10-year yield went from 3.95% as the CPI data was published, to 4.10% by the close. As I write, yields are up to 4.15%. Meanwhile, the S&P500 is pretty much unchanged.

So, for equities and bonds, what was a bullish driver has become less so now. Investors have had quite a lot of the ‘immaculate disinflation’ narrative in the past weeks and corroborative data is not new information.

Moreover, there is a danger that disinflation (a slowing in the inflation rate) is not so immaculate. The description attempted to convey the idea that, while the inflation component melted away, growth could and would remain strong. This is where last week’s news flow about falling inflation begins to turn counterproductive. China also released July inflation data last week and that was unambiguously deflationary (rather than disinflationary). On a year-on-year basis, consumer prices fell 0.3%. Yet again, producer prices were also down 4.4% year-on-year. We write about some longer-term aspects of the China story below in a separate article.

The problem is that it is weak growth which creates the falls in prices. One can argue that China’s problems are a benefit to western consumers and businesses. But, as we point out in the article, businesses that compete with Chinese exporters are finding they are losing pricing power, while suppliers of commodities to China are experiencing a sharp slackening in demand. Thus, weak growth in China may be transferring to the rest of the world.

Oddly perhaps, in the energy markets, OPEC’s attempts to tighten supply has borne fruit with a rise in global oil prices in the past month. This has led to a (remarkably immediate) follow-through here in the UK, where petrol and diesel prices have risen by about 10p a litre. The same is occurring in Europe and the US.

Again, it’s not just oil; a strike by Australian natural-gas workers caused a 40% rise in European near-term delivery natural gas prices. Australia is the world’s largest supplier of liquid natural gas (LNG), most of which goes to Asia (especially Japan). However, our biggest suppliers (US and Qatar) can also supply those markets so it has had quite an impact as LNG markets are proving more global than they perhaps used to be.

And in food markets, the typhoon season has pushed up rice prices.

Of course, central banks and investors like to look at inflation with food and energy stripped out precisely because they are volatile components that usually have a less structural impact, as they usually fall as quickly as they have risen. However, in the current situation, as global economic growth may be coming under threat, investors worry that a renewed – even if temporary – price push from the volatile end of the inflation spectrum may cause a delay in the path towards easier monetary policy.

Back at home, the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyor’s report on the housing market continued to show a likelihood of further house price falls which, in earlier years, would be a harbinger of very difficult economic times. Yet the UK economy put in yet another quarter of growth, albeit anaemic, at +0.2%. The really surprising aspect was that July manufacturing and construction output (contained in a separate report) was very strong at +2.4% and +1.6% month-on-month, respectively. That echoed the construction purchasing managers’ index (PMI) from the previous week, which showed a totally surprising shift into growth territory at 51.7 (50 marks the divide between contraction and expansion). Perhaps unsurprisingly, bond yields shifted sharply higher last Friday after the data, with the 10-year testing 4.5% and the two-year back at 5%. Neither has yet broken beyond the highs of the past month, however.

While estate agents may be pessimistic, a lowering of general house prices may be offsetting the rise in interest costs. Perhaps housing may be approaching (just about) affordable territory for the huge cohort of young adults who have been trapped in the rental market. In that case, housing activity could have a structural support (!).

August is generally a quiet month, with many taking a holiday. Historically known as the ‘silly season, when stories of little importance would be given headline status. In recent years, August has felt more like business-as-usual, but market liquidity can still be somewhat reduced and, if news is really important, can lead to sharp dislocations.

So far this month, the stories are not unimportant, but neither are they earth shattering. Volatility has picked up a little but is still way down from last year and even the first half of this year. So, it’s probably best not to make too much of the little worries that are crossing the path last week.

We need to talk about China

China’s economy has sputtered again. Data released last week showed consumer prices fell 0.3% year- onyear in July. Producer prices were even lower, falling 4.4%. That might sound like a strange thing to complain about, given the west’s ongoing battle with high inflation; but China did not experience the same wave of post pandemic inflation, and now deflation is a bad sign for the world’s second-largest economy. It shows weakness in consumer demand, which will likely mean slower growth down the line.

The wider context is that China has been the biggest economic disappointment of the year so far, at least when compared to initially heightened expectations. After Covid regulations were loosened and policy stimulus seemingly forthcoming at the end of 2022, most thought a sharp bounce in activity was a foregone conclusion. However, business activity failed to generate significant momentum, as reflected by poor earnings of listed companies and with the property sector proving to be an enormous and continuous drag.

It’s not all areas that are sluggish; judging from indicators like movement and travel, Chinese citizens are indeed taking advantage of post-pandemic rule changes, and consumer services have been reasonably upbeat. The same applies to targeted infrastructure investment, which still seems to be forthcoming.

Nevertheless, weakness in consumer prices is concerning, given Beijing’s focus on stimulating domestic demand. At the same time, businesses should be benefitting from recent interest rate cuts and tax incentives. But for now neither of these are adding much positive activity.

Although China has been trying to increase the share of domestic demand in the overall economy, businesses are still far more strongly impacted by external demand and, in terms of the latest disappointment, it is clear that weakening exports are playing a big role. Exports were 14.5% lower last month than the year before. The decline was steeper than economists expected, and the worst drop off since the start of the pandemic in February 2020. Slack goods demand elsewhere in the world is a big factor: after two years of price rises, western consumers and businesses have significantly tighter budgets.

That does not explain all of the weakness, though. One of the most remarkable observations about developed economies (primarily the US) in recent months has been the resilience of consumers against seemingly tough conditions. But despite US demand surprising to the upside, Chinese exports have surprised to the downside. Moreover, imports into China have also been significantly weaker than expected, falling 12.4% year-on-year in July against expectations of a 5% decline. It was China’s biggest import decline since January, when a brief Covid resurgence hit the mainland, and one of the biggest falls in recent years.

There are after-effects of the pandemic in these trends. When supply chain problems struck a few years ago, companies built up inventories to avoid losing out on sales. But as we have written much about recently, weaker demand in the developed world (thanks to cost-of-living crises, and demand shifts from goods to services) meant a reversal this year. Companies both in and outside of China have drawn-down their excessive inventories, reducing trade volumes.

At the same time, the US-China trade relationship shows no sign of improving, and the de-linking of the world’s two largest economies continues. When ex-president Trump initiated his trade war against China, many production-focused companies accelerated their moves away from China (which were already happening, thanks to higher Chinese wages) to other parts of Asia.

The process is continuing. Last week, President Biden signed an Executive Order which puts more barriers between the two economies, implementing new restrictions on US investment in high-tech Chinese companies. The order will set up a new screening process that will probably limit how private equity and venture capital firms can invest in Chinese companies focused on technologies with military applications, like quantum computing, artificial intelligence and advanced semiconductors.

The barriers to investment in China have led to western money being kept at home or flowing to other nations, and that also means more competition for Chinese producers. Together with the slowdown in overall global demand, this has led to a meaningful fallback in exports – which have even taken a hit in local renminbi terms, despite the currency’s slide in value.

Considering the US-China relationship, and its effect on the latter’s economy, brings us to a key point: it appears China’s internal politics have been an increasing factor in the disappointing economy.

This was obvious during the pandemic, when the cycle of lockdowns kept 1.4 billion Chinese citizens from going about their regular lives. During that time though (and indeed, well before) the Communist Party repeatedly asserted its control over China’s private economy. This was seen through actions like cancelling companies’ stock market debuts (initial public offerings), allowing pressure to pile up on property developers, or declaring the entire private education industry unprofitable by law.

While these developments are not exactly out of character for China, their close occurrences – and their correlation with Xi Jinping’s accumulation of power – have spooked many would-be risk takers. The mandatory party representation within private companies has removed the sense of entrepreneurship in many of China’s growth-focused companies, while the risk that profits might be taken or banned entirely has discouraged high-risk value creation. In a sense, this is exactly what Xi and his comrades intended – particularly with regards to highly-indebted property companies – but the double edge is that it removes the dynamism which had propelled China for so long.

It was interesting to see that, just as data about China’s disinflation was being announced, Beijing was telling economists across the country not to talk about deflation or negative growth trends. Censorship is, of course, nothing new in China, even when it comes to academic research, but this particular diktat feels a lot like an admission of weakness. The regulator has apparently asked academics and private researchers to present negative findings in a good light.

As we wrote recently about China, its economic problems have never been about lacking potential. The question is whether the government is willing or able to unlock it, and as yet it remains unanswered. At the end of July, Beijing called for strong countercyclical measures to arrest a recent decline, but as (by now) usual, the details on what this actually means are lacking. Policymakers want to boost short-term growth but are unwilling to loosen their grip on the private sector to do so.

China still has potential to rebound in the nearer term. The ingredients for a decent economic and market recovery are there. What increase in political meddling means is that, for foreign investors over the longer term, returns on Chinese assets are difficult to assess. Even though economic growth will come through, there is no guarantee this will translate into enough profit to justify investment, thanks to the unpredictability of central government. There are growth opportunities in China; Beijing only needs to decide they are in its interest.

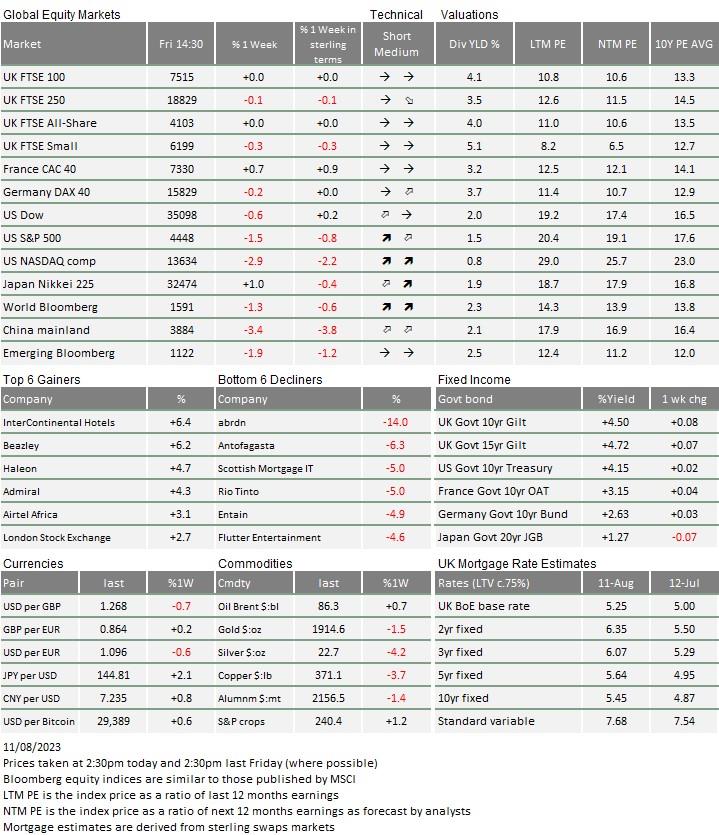

* The % 1 week relates to the weekly index closing, rather than our Friday p.m. snapshot values

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.