Published

29th August 2023

Categories

Perspective News, The Cambridge Weekly

Share

The Cambridge Weekly – 29th August 2023

Transcontinental growth divergence

We don’t seem to be able to get away from writing about how bond yields have been driving equity markets due to their influence on underlying valuation dynamics. We wrote about it the previous week, on many occasions over the past two years, and we have to say that last week is no different. However, whereas we have previously generally commented on yields rising, yields ended lower last week.

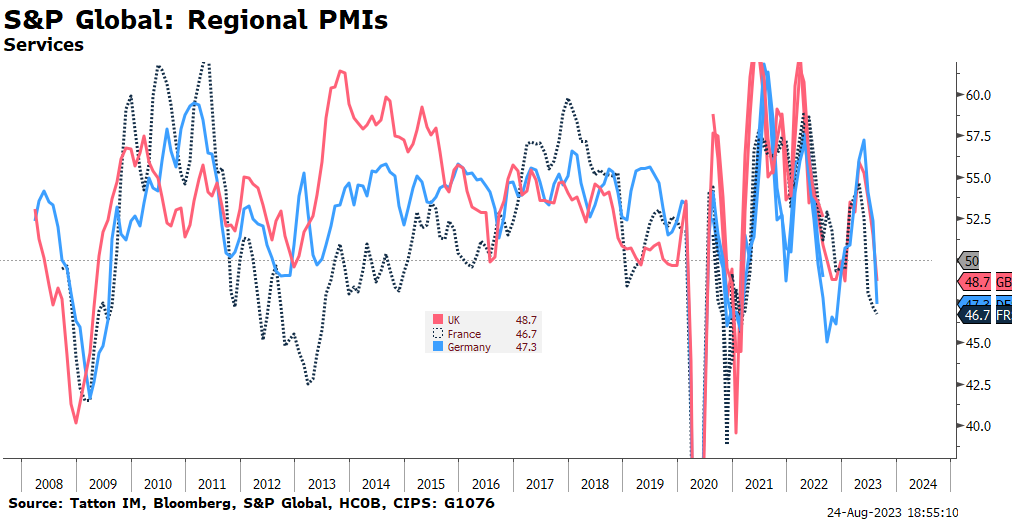

The previous week, the upswing in yields came on an improving US growth outlook. Last week, the catalyst for the yield drop was unexpectedly weak ‘flash’ Purchasing Manager Indices (PMI) survey results (collected by S&P Global). The worst of these forward-looking measures of business confidence were focused on services in Europe and the UK, and we look at these in more detail in the first of our articles. European data has been poor for well over a year now, but there had been hope that thus-far resilient services would underpin weak manufacturing, but now it may be travelling the other way.

In the US, services at 51.0, were also weaker than expected but still managed to remain above the neutral 50 level. Indeed, recent US data may have felt mixed but the combination indicators suggest growth is solid to strong.

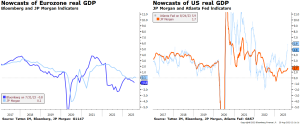

The charts above show current estimates of Eurozone (left) and US growth (right), with the Atlanta Federal Reserve’s US indicator (light blue) pointing sharply upwards. We suspect this may come down quite sharply again soon, given its increased post-pandemic volatility record, but visually the indicators suggest there is little doubt about the different trajectories of the two transatlantic powerhouse regions.

Some of those differences can be traced back to energy prices still remaining more of a burden for Europe’s manufacturers, especially for natural gas and electricity. Sentiment improved through the first half of this year as gas prices declined but the recent uptick in both oil and gas prices is a blow. Meanwhile, the auto sector (much more important in Europe than the US) is also feeling a sharp pinch, with Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers gaining substantial market share at home and getting an easier ride in Europe than in the US.

Unusually, Germany is the focal point of European weakness. This is all too logical after the double whammy of losing both their access to cheap Russian energy and increased reliance on exports of cars and machines to China. Olaf Schulz’s rating as Chancellor has taken a sharp swing down in recent weeks, while talk is growing of increasing the fiscal deficit. However, expand deficits will be a difficult and long-winded process after the combined hits of the pandemic and Ukraine-Russia war.

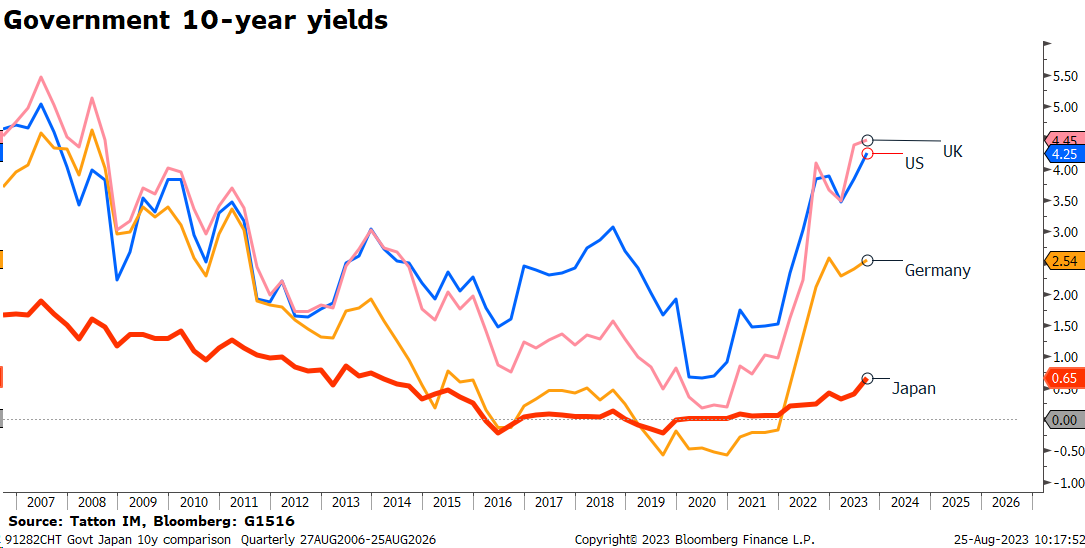

Given that the European Central Bank (ECB) has moved rates up from below 0% to 3.75%, it is much more likely that pressure will grow on the Governing Council to cut rates at the first sign of an alleviation in inflation pressure. The problem for them is that real bond yields (after subtracting inflation) may finally be positive (the 10-year German government inflation-linked bond has a real yield of 0.18%) but nowhere near as positive as in the US or even the UK, where they are nearing 2%. We know from the past that the ECB will not flinch from acting if a crisis ensues, but it is less likely to act without a clear crisis and given its balance sheet remains inflated due to quantitative easing (QE) its only policy alternative may be to cut rates this time around.

It may also be hamstrung by inflation pressure re-emerging which could happen if the euro were to come under more pressure and given the widening gap in real yields to the US, euro weakness is a distinct possibility.

On the flipside, Europe’s economic weakness has had surprisingly little impact on either equity or credit markets. Commentators have pointed to the relatively more benign government bond market which helps forward valuations of profits. With few new high-yield bonds available to buy in either Europe or the US markets, demand has to necessarily focus on what is already being traded – and demand keeps yields down. As a result, given that there aren’t any new issuances and none is likely for another month, Bloomberg has decided to cease its daily report on new high yield bonds.

However, a thin market can be deceptive and potentially volatile. A lack of supply can keep prices high, but it can also make the impact of bad news greater and, of course, a weak economy is generally not great for prospective revenues and profits.

It is quite possible that investors believe the current pessimism over pan-European growth will pass much like it did last year in the US. Turning to Europe’s biggest swing in demand factor, China, the equity market there remained weak last week despite rumoured “support” buying from government-influenced investors. However, expectations are still strong that Beijing is piecing together a wider fiscal package. That would certainly improve sentiment for European exporters.

Last week, the central bankers had begun their weekend in Wyoming’s Jackson Hole. The strap-line for this get-together is “Structural Shifts in the Global Economy” so there will be a concerted effort not to talk about near-term policy. Nevertheless, we hope we will get more clarity on how central banks view the impact of their still-huge balance sheets. Clearly, with the ECB facing another slowdown, it would be interesting to know how this affects their viewpoint on current policy alternatives.

Economic divergence between regions is not unusual, and Europe is prone to having bouts such as the euro crisis. We don’t think something as serious as that is about to happen, but there is little doubting that Europe has less resilience than the US currently, due to the conspicuous lack of growth momentum. This probably means pressure on the US dollar to strengthen at least for a time and, historically, that has coincided with increased global risks. In particular, it has a tendency to put pressure on credit spreads as a stronger dollar leads to shortages of dollar liquidity away from US shores. That, in turn, can create a less positive outlook for global risk assets – corporate bonds and equities.

However, if no actual credit event arrives, a less positive environment may just mean increasing market volatility but little direction on average. August has already provided plenty of that and as we head towards its close, is going nowhere more rapidly.

Not much between the EU and UK

We wrote the previous week that, after being the best performing currency of the year so far, sterling looked vulnerable. This sentiment was echoed by the Financial Times last Monday and, as if like clockwork, the pound fell against the US dollar into midweek. The overall fall is very slight – with the sterling-dollar rate being only just below where it started last Monday – but this covers up a sharp intraday drop during last Wednesday’s trading.

The fall was incited by the latest UK business sentiment surveys, which were unequivocally bad. The flash purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs), a forward looking indicator measuring business confidence, for August came in significantly below economists’ expectations, and paint a very gloomy picture of the British economy. The composite PMI fell to 47.9, its lowest level in 31 months. A PMI above 50 usually suggests expansion ahead, while anything below that points to contraction. Manufacturing recorded a dour 42.5, below both the projected level and last month’s figure.

Meanwhile, the all-important services sector – which represents around 75% of the UK economy – fell to a downbeat 48.7, against expansionary expectations of 51.

S&P Global think this could translate into a 0.2% decline in the UK economy for the current quarter, with chief business economist Chris Williamson calling a downturn “inevitable”. Punishingly high interest rates were a clear theme in the PMI reports. British firms are squeamish about investing in the current climate, thanks to sharply higher financing costs and budget-constrained consumers. This weakness has thankfully gone hand-in-hand with reduced inflation expectations, causing markets to reassess the likelihood of further Bank of England (BoE) rate rises. But as we wrote the previous week, this puts downward pressure on sterling, since an aggressive BoE seemed to be the key factor supporting the currency.

The UK has a recent reputation as a laggard among major developed economies, but as the chart above also shows, this time around Britain was not alone in its poor output – nor was it even the worst. European PMIs showed their worst readings in nearly three years, amid a sharp deterio-ration in consumer confidence. The preliminary Eurozone composite PMI for August fell to 47, below expectations of 48.5 and the lowest figure since November 2020. Manufacturing actually surprised to the upside, though the reported 43.7 is still very firmly in contractionary territory. Services were expected to post a practically neutral 50.5, but instead delivered the first contraction in eight months, with a reading of 48.3.

As in the UK, the currency value bore the brunt of Europe’s poor outturn. The euro fell against the dollar last Tuesday, and had another spike down during last Wednesday’s trading – though the latter recovered to close slightly higher. This extends a month of declines against the US currency, owing to the diverging growth prospects on either side of the Atlantic. Interestingly, currency pressures meant British and European stock markets remained stable in spite of weakness. Equities were also helped by falling bond yields – a reflection of lower inflation and interest rate pressures.

That being said, the divergent economic data – resilient in the US, gloomy in Europe – is clearly feeding through into corporate earnings expectations. Healthy growth in earnings is now expected in the US (albeit with a distinctly rosy view of 2024’s prospects) but not in Europe, and this latest PMI data suggests profits could be even worse than current analyst expectations. Continued weakness in manufacturing is a big part of the problem. Sentiment was slightly better than expected – suggesting some stabilisation for the sector – but it had been hoped that services would remain buoyant allowing manufacturing to regain some strength. Now it seems the negative environment is also dragging down service providers.

Germany is at the heart of Europe’s struggles. Manufacturers have long been under pressure in the continent’s largest economy and, while there was slight improvement from a dire July, the 39.1 PMI points to severe contraction. The hope was that services would come to the rescue, but things instead look the other way around. Sentiment in that sector dropped too, resulting in a composite PMI of 44.7, the lowest reading since May 2020 and sharply below expectations.

Most worryingly, survey data suggests price pressures have increased in the German services sector, despite a worsening outlook for demand and activity. There is thankfully no sign of broad-based price increases, but services inflation remains uncomfortably high due to increased wages. It is likely that dour business sentiment – particularly around new orders – will put pressure on employment in the coming months. But for now, a tight labour market is still pushing up costs.

This puts the European Central Bank (ECB) in an unenviable position. Just like the BoE, a deteriorating growth outlook has decreased expectations of an interest rate hike at the September meeting (which markets now price as roughly 50/50). But again like the BoE, labour shortages – particularly in Europe’s peripheral nations – mean the economy is vulnerable to spiralling inflation. If input prices were to increase again, as we have seen some signs of already, inflation could easily increase once more.

For Germany specifically, there are questions about what this means for fiscal policy and bond prices. As the continent’s historical growth engine with an (almost) annoyingly prudent fiscal track record, German bonds trade at a premium over other Eurozone bonds. But with grim growth prospects and a tight labour market, investors might question whether this premium is justified. The spread between German and Italian bonds at 10-year maturity is now less than 1.7%, despite a general move up in European yields. The spread characteristically widens as yields go up, but this has not happened – suggesting a re-evaluation of relative credentials.

From an equity perspective, economic weakness – if it does indeed come through – might not be as painful as feared for the UK or Europe. Currencies (particularly sterling) look vulnerable but stocks this side of the Atlantic already trade at substantially lower valuations compared to the US. While that is hardly anything to get excited about, it might at least insulate investors from nearby growth shocks.

Is Japan’s central bank ice age melting at last?

Japanese bond yields rose to their highest level in nine years this week. After a global bond sell-off over the last few weeks, and a change in Bank of Japan (BoJ) policy that some commentators described as game- changing, the yield on 10-year Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) has risen to the ‘unaffordable’ level of – wait for it – 0.68%. UK and US investors would be forgiven for being a little underwhelmed by the not very massive return. US 10 year Treasury yields, the reference point for global bond markets, peaked above 4.3% at the start of this week, while our own 10-year gilts reached higher than 4.7% last week.

Nevertheless, this is a significant uptick in the Japanese context. Japan’s bond market is famously boring, a reflection of its long-stagnant economy. Historically low growth, inflation and interest rates have kept yield volatility low to non-existent for years (JGB yields have a range of just over 2% going back 25 years, during which US yields have varied by more than 6%).

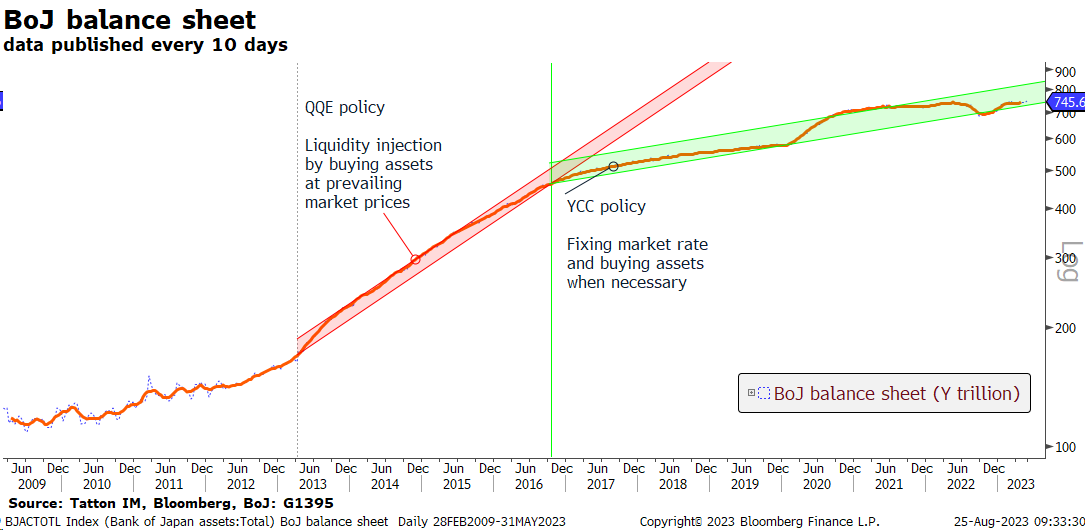

This stability has been officially enshrined since 2016, when the BoJ began its policy of ‘Yield Curve Control’ (YCC), replacing the previous policy of ‘Quantitative and Qualitative Easing’ (QQE). This meant restraining the yield on the benchmark 10-year JGB to a ‘target’ rate around 0% and from rising above a specific yield level – previously 0.5%. This would be achieved if necessary by buying as many bonds as required to make that happen.

The shift may have looked rather technical but marked quite a change in the pace of monetary injection, effectively slowing the central bank’s liquidity push. The chart below shows the differing trajectories for the BoJ’s balance sheet:

As we can see, recent moves have achieved near-stability (no growth) in the balance sheet and now the intention is a gentle removal of control.

At the end of July, though, the yield ceiling was raised. BoJ Governor Kazuo Ueda announced the 0.5% leeway around the official zero target would stop being treated as “rigid limits”, and now merely be “references” for bank operations. The BoJ’s highest rate at which it bids for fixed-rate JGBs every day would rise to 1% from the previous 0.5%.

Many analysts suggest this is effectively the end of Japan’s YCC, and some feared the effect this might have on global asset markets. But Ueda remains adamant this is just a tweak to YCC, rather than its death knell. According to Ueda the policy remains in place, just with a little more leeway. There is precedent for this too: the initially tight target band for JGB yields was loosened in early 2021 and again in late 2022.

Bond movements in the last four weeks have backed up the BoJ’s assessment. As one might expect, JGB yields spiked immediately after the announcement, as bond traders tested the BoJ’s resolve in its policy change, reaching the highest point since 2013. Decade-high yields notwithstanding, the market response has been fairly muted, all things considered. If markets really thought YCC was on its deathbed, we might expect sterner tests of the BoJ’s limits – resulting in rapid selloffs and yields close to the stated cap. This is especially so in light of the renewed pressure on US Treasury yields, which have risen by more than 0.5% in the last month alone.

As it happens, the BoJ has only deemed it necessary to intervene twice, both times after yield jumps of five basis points (0.05%). In line with the stated aims of the YCC tweak, these interventions have been to slow the pace of yield rises rather than curtail the absolute level. This has helped maintain a sense of calm in Japan’s bond market – placating those who were starting to worry about monetary laxity without robbing the economy of much-needed support.

The feeling seems to be that JGB yields have room to manoeuvre, but without ringing the alarm bells. Further increases would make sense too, given Japan’s recent inflation numbers. Headline inflation has been holding steady at or around the 3.3% mark for most of the year, in a marked change to decades of deflation. Price rises have been consistently above the BoJ’s stated 2% target and for the last two months actually higher than US inflation.

A few economists have warned inflation in Japan could become ‘sticky’ unless the BoJ tightens quickly. That is exactly what happened in the west in the past two years, with price rises becoming entrenched after central banks were accused of falling ‘behind the curve’. In particular, the YCC has made the yen extremely sensitive to overseas interest rates, which is one of the reasons the currency has declined so markedly this year. This exacerbates imported goods inflation.

That said, Japan still lacks the main inflation pressure that has worried western central bankers for so long: rising wages. Tellingly, Japanese core inflation – excluding volatile elements like food and energy – was lower in July than the month before, with many analysts suggesting the country’s inflation impetus had already peaked. Indeed, in stark contrast to the US and UK, the BoJ has been actively trying to encourage wage rises to spur its economy.

Crucially, wage-setting behaviour – typically extremely conservative in Japan – needs to shift up a gear before the rate-hiking cycle ends in the west. As we noted last week, the yen’s weakness has actually been a big help in that respect. Corporate governance structures have improved greatly in recent years, allowing Japanese companies to take greater advantage of profit opportunities. A falling yen – and the increased export price competitiveness it brings – is one such opportunity, and a big one at that. Sure enough, Japanese exporters have grown massively as a share of the economy, and improved profitability is finally filtering through into wage levels.

It is therefore far too early for the BoJ to think about tightening policy in earnest, despite fears about abandoning YCC. It knows full well that a weaker currency and lower financing rates are improving Japan’s attractiveness both as an exporter and an investment destination. Policymakers also know inflation could quickly give way to deflation if global financial conditions change. A tweak to YCC is far from the end of Japan’s accommodative policy. This is good news for western investors, as JGBs so often act as an anchor in global bond markets. Higher Japanese yields are an important sign for the global economy, and thankfully one that is unlikely to destabilise markets.

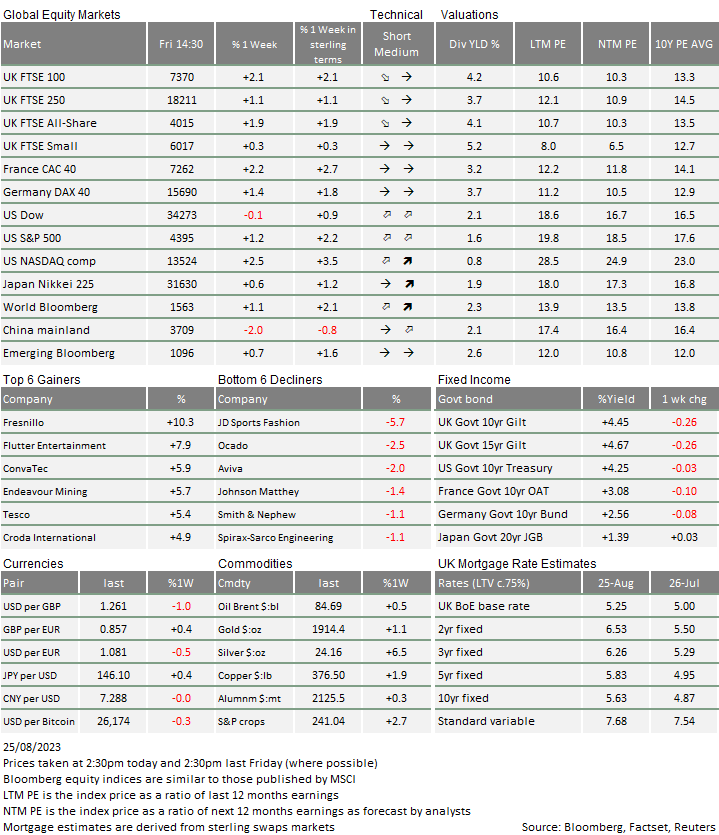

* The % 1 week relates to the weekly index closing, rather than our Friday p.m. snapshot values

If anybody wants to be added or removed from the distribution list, please email enquiries@cambridgeinvestments.co.uk

Please note: Data used within the Personal Finance Compass is sourced from Bloomberg/FactSet and is only valid for the publication date of this document.

The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.